Author’s Note

I wrote this piece for a large publication in honour of the upcoming National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Each year on September 30, I find myself returning to the question of how we remember, how we honour, and how we act. This day is not just about wearing orange or acknowledging history — it is about making space for the truths of survivors, for the memory of those who never came home, and for the responsibilities we all share in carrying reconciliation forward.

For me, reflection often begins with place. The Grand River has been both a teacher and a mirror — reminding me of what endures, even in the face of broken promises and loss. In writing this, I wanted to offer something that speaks to the importance of listening to land, to people, and to the responsibilities that come with both.

My hope is that readers will take this day not only as a time to remember, but also as a time to act: to learn whose land they are on, to listen when Indigenous voices speak, and to consider how reconciliation might take root in their own lives.

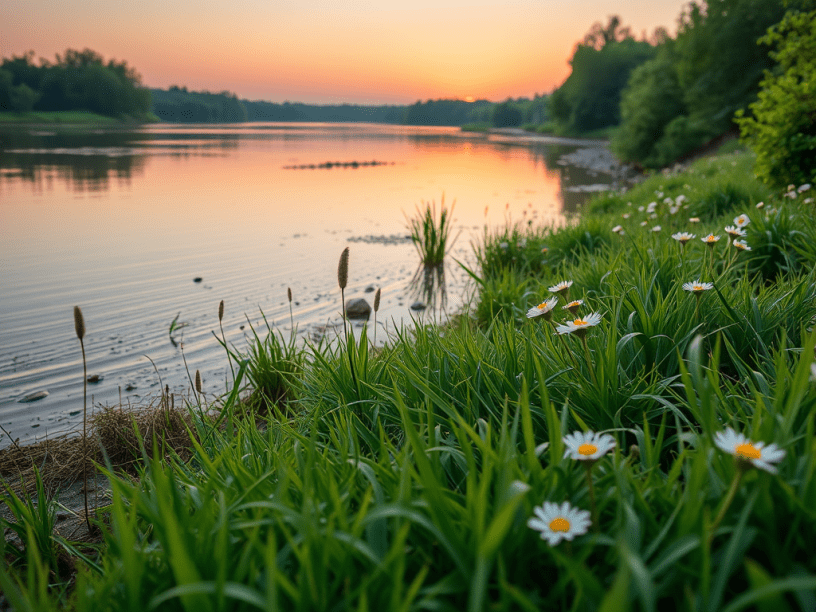

At early dawn, I find myself on the banks of the Grand River, where the first light falls across the northern edge of Six Nations. The grass is damp beneath my feet, and the air carries a coolness that settles me into the quiet of the morning. I come here to be reminded of what endures — the river that has carried the Haudenosaunee for centuries, and the lessons it still carries for me. A peaceful breeze drifts across the water, the air filled with the rush of the fast-moving current, the call of a bird, and the steady chorus of crickets. The faint, sweet fragrance of wildflowers drifts in with the wind, subtle yet grounding, as if the land itself is breathing with me. Whatever traces of urban sound reach me from the distance fade into nothing against this symphony of land and water. In that quiet balance, I can imagine what the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, and Tuscarora found in these grasslands and rivers so long ago. The peace, the medicine, the balance — a way of life rooted in relationship with the earth, long before 1784 when the British claimed and reclaimed this territory. That harmony was disrupted by centuries of broken promises, displacement, and development — yet the river still carries their presence, and their struggle to remain. Here, there is a balance I cannot seem to find anywhere else.

Years ago, I came to these banks while covering the 1492 Land Back Lane dispute. Returning now, I feel the same pull of river and land, steady and unbroken. I remember the way the sun fell across the water after long days of listening, the way smoke curled up from fire pits where stories were shared, the way silence itself became a form of teaching. As a filmmaker and journalist, I spent years listening to land defenders from Six Nations, learning their stories, and witnessing their determination to protect their homes and their medicine. What began as observation grew into friendship; what began as listening grew into allyship. I was welcomed into homes, into backyards, into spaces of trust along the Grand River. Between quiet conversations and moments of reflection, I came to understand not only the depth of the Haudenosaunee connection to this place, but also the urgency of protecting it.

That understanding was not always easy. I had to confront the ways I benefit from land taken by force, and the privilege of being able to step away when others cannot. There were moments of discomfort and doubt, but they were necessary — reminders that reconciliation is not about my comfort, but about responsibility. Sitting at kitchen tables where laughter and teaching flowed together, or walking across fields where each plant was named as medicine, I learned that the fight for land was never only about property. It was about survival, culture, harmony, and medicine. It was about futures yet to come.

Over the years, people I once interviewed became collaborators, friends, and family. From them, I learned that stewardship requires action, not just words. Inclusion means listening, not just acknowledging. Reconciliation is not something we can legislate into existence; it may come only through a shared effort to protect the land, water, and medicine that, in turn, protect us.

On this Truth and Reconciliation Day, I return again to the Grand River in my mind. I feel the coolness of the dawn air, hear the steady rush of water against the banks, and carry with me the voices of those who welcomed me into their struggle. Its flowing waters hold memory, resilience, and responsibility. To honour them, and to honour the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, is to recognize that reconciliation begins with place — and with how we choose to live with it. Truth and Reconciliation Day asks us not only to remember, but to act: to learn whose land we live on, to support Indigenous stewardship, to show up when invited, and to help protect the places that hold memory and medicine for future generations.

Stay Connected — It’s Free

Subscribe with your email below to unlock member-only content. No cost, just insight and stories delivered straight to you.

I DIDN’T PLAN TO BECOME A TEACHER: The Students Who Made Me Stay

I didn’t become a teacher because I planned to. I became one because I stayed. Because I said yes often enough. Because students like Alex and Clare taught me that education is not merely academic—it is relational, fragile, and profoundly human.

RAISED BY PLACES UNSEEN: The Quiet Way Borneo Found Me

I arrived in Kota Kinabalu under a veil of night. The airport was modest, its walls carrying a patina of age that felt unexpectedly comforting. It didn’t strive to impress; it felt lived-in, a doorway used by generations of travellers before me.

PART 3 – NO PERMISSION NEEDED: What Was Once Shame Has Become Pride

What began as innocent play, the joy of dressing up and pretending, soon curdled into confusion and punishment. My parents’ gentle corrections hardened into anger, their voices faltering with something more akin to unrelenting impatience. My pleas — small, wordless, desperate — were dismissed as misbehaviour. How could I have explained, at four or five…