PROLOGUE

Earlier in the month, Harriet Tubman was overtaken by a feeling she could neither explain nor ignore. Her brothers—Robert, Benjamin Jr., and Henry Ross—were in danger. She did not hesitate. A trusted friend was asked to write a coded letter to Jacob Jackson, a free Black man in Maryland. The message was brief and urgent: she was coming; they must be ready.

Tubman trusted instinct the way others trusted maps. Every rescue she led followed rules learned at terrible cost. Delay invited disaster. When the hour came, she would not wait.

She arrived on December 24 to news that escalated the urgency of her expedition. Her brothers were to be sold the day after Christmas. Tubman sent out word to gather. She would move north that night—Christmas Eve. They were to meet after dark and begin at once, walking forty miles to their father’s cabin.

At the appointed hour, Benjamin Jr. and Henry were waiting, along with John Chase and Peter Jackson. Benjamin Jr. had brought his fiancée, Jane Kane, disguised as a man. One figure was missing. Robert had not come.

Tubman knew the cost of hesitation. She also knew the cost of leaving. Believing he might still reach them at their parents’ home, she made the choice that would haunt any leader: she moved on without him.

Robert had been delayed by his wife, who had gone into labour, unaware of his plan to escape. Within days, he would be sold south—likely forever—yet his family lay before him, newly broken open by birth. A daughter was born.

At dawn on Christmas morning, Robert slipped away. He told his wife he meant to “hire himself out for Christmas Day.” She did not believe him. She watched him go knowing what his leaving meant.

He walked to his parents’ home in Poplar Neck, Maryland, and found Harriet, Benjamin Jr., Henry, and others hiding in the fodder house, a low shed heavy with the smell of hay and rain-soaked straw. From there, they watched the cabin from a distance—close enough to see it, too close to risk being seen.

Tubman sent two men to quietly alert her father. They were told not to tell her mother that the children were nearby. Her father brought food and returned without a word.

From their hiding place, they watched their mother step outside again and again, peering down the road, searching for the sons meant to come home for Christmas dinner. They did not answer her cautious, curious inquiries. They could not.

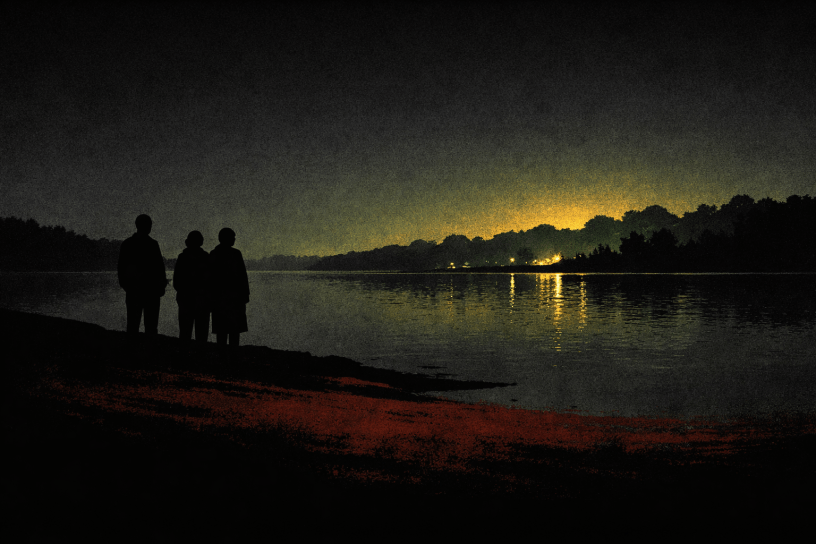

That night, Tubman led the group north. Every mile carried the risk of capture. Every sound could be a footstep; every shadow, a hand reaching out of the dark. North was not a place so much as a direction—one that had to be followed without pause or regret.

They passed through Wilmington and reached the home of Thomas Garrett, a stationmaster of the Underground Railroad. He fed and clothed them, gave money for shoes, and arranged a carriage to carry them farther north, into Pennsylvania, where even the ground beneath their feet felt uncertain.

By December 29, they arrived in Philadelphia and were received by William Still. In his presence, names were laid down and replaced. Robert Ross became John Stewart. Henry Ross became William Henry Stewart. Benjamin Ross Jr. became James Stewart. Still recorded their arrival, fed them, and provided money for the next leg of the journey, as if each new name might help anchor them to freedom.

At the turning of the New Year, Tubman and those she guided reached St. Catharines. They crossed a border that could not be seen but could never be crossed back.

Nearly a decade later, in 1863, William Henry Stewart would recall that journey and confirm that ten freedom seekers fled Maryland on Christmas Day in 1854, led by his sister—called “Moses”—who walked them north through fear, silence, and irrevocable choice.

That crossing did not end the story. It settled it into the ground.

UNFINISHED PROMISES

Growing up in St. Catharines, I understood—long before I could fully articulate it—that the city carried a history far larger than its size. This was not taught to me as a distant footnote, but as something living and present: St. Catharines as a terminus on the Underground Railroad, a place where enslaved Africans and African Americans crossed into what they hoped would be freedom. Harriet Tubman’s time here was not abstract history; it was part of our local inheritance.

For many fleeing enslavement, British North America represented salvation. The law did not permit slavery, and the territory was seen as beyond the reach of slave catchers—a place where families might finally live without the constant threat of violence and capture. St. Catharines, in particular, became a site of refuge, organizing, and rebuilding. It was a place where hope took root.

But hope and reality are not always reconcilable.

While Canada offered freedom from enslavement, it did not offer freedom from bigotry. Freed Black people who settled here encountered segregation, economic exclusion, restricted access to education, and pervasive social hostility. Schools were often segregated. Employment opportunities were limited. Land ownership was precarious. Freedom existed, but equality did not—and in many ways, still does not.

This distinction matters, especially in a country that often defines itself in contrast to the United States. Canada is frequently framed as the moral alternative, the “better” place. Yet Black communities were not simply welcomed into an inclusive society; they had to fight, organize, and advocate for dignity, safety, and opportunity. For many, the journey from enslavement to self-determination did not end at the border. Arrival in British North America often felt less like an ending than a refashioned—if unsettlingly familiar—terrain.

What has always struck me is how little of this history is widely known, even locally. Black communities in and around St. Catharines built churches, schools, businesses, and mutual aid networks. They contributed labour, culture, leadership, and resilience. Yet much of this history has been erased or compressed into a single moment—the Underground Railroad—rather than understood as an enduring presence. St. Catharines was a cradle of Black settlement, resistance, and community in Canada, and too many of these stories have faded into obscurity.

This erasure is not trivial. When we fail to remember Black history fully, we lose not only accounts of suffering, but of strength. We overlook the resistance, creativity, and community-building required to survive—and to thrive—in a society that promised freedom while withholding equality. When history is flattened or forgotten, it becomes easier to deny the systems that persist today.

Just a few hundred meters from the MTO building in St. Catharines stands an unassuming church on a busy road. Known today as the British Methodist Episcopal Church, or Salem Chapel, it marked the end of the line for African-American freedom seekers—the destination Tubman sought on that winter night in December 1854. Modest beside the city’s larger churches, it represented something far greater: the promise of safety for thousands.

Inside, artifacts from the church’s founding and the Underground Railroad line the nave. Sitting in silence among them, I feel the weight of lives shaped by courage and loss, by hope tempered with vigilance. The proximity of this place to the machinery of modern governance only sharpens the contrast. History is not distant here. It presses close.

That understanding shaped my commitment to social justice. Learning early that freedom can coexist with institutional oppression made it impossible to accept simple narratives of progress. It taught me that progress is not self-sustaining—that it demands vigilance, memory, and action. It also taught me that institutions matter: laws, policies, and public systems can either entrench inequality or dismantle it.

This brings us to the present.

The cost of forgetting Black history is not symbolic. It is measurable. It appears in disparities in policing and criminalization, unequal access to healthcare, housing insecurity, and inequitable educational outcomes. These inequities do not arise from individual failure. They persist because history shapes systems, and systems shape lives.

When Canada forgets—or selectively retells—its own history, it becomes easier to dismiss these disparities as anomalies rather than patterns. It becomes easier to claim progressiveness without accountability, inclusion without examination. Remembering Black history honestly challenges us—not because the past defines us, but because it instructs us.

Black History Month is often framed as a time for celebration, and celebration matters. But it is also a time for reflection: for asking whose stories are remembered, whose are missing, and why. In places like St. Catharines, the legacy of Black freedom seekers is not simply a story of arrival, but of perseverance. It reminds us that justice is not a destination reached once, but a responsibility carried forward.

Remembering this history fully is not about dwelling in the past. It is about ensuring that the systems we uphold today move us closer to the freedom that was promised—and not yet fully realized.

This essay was written on assignment for a government publication.

On Not Disappearing

I am not good at making lifelong friends. My record is uneven, marked by distance and missed chances. Going stealth would have only deepened that pattern. More importantly, it would have meant abandoning the mercy, empathy, and action shown by the people who stood beside me. I needed their proximity—not just their support, but their…

JUSTICE ENDS WHERE POLICING BEGINS: The Shameful History of Policing The Gay and Trans Community in Canada

Policing reform is routinely framed as a matter of training, oversight, or inclusive language. None of this resolves the central contradiction exposed by decades of violence against trans people: policing is a system built on discretion, not equality. It decides who belongs, who is suspect, and whose suffering is credible.

ROT AT THE CORE: How Transphobia Persists in Niagara’s Policing Culture

The former president of the Niagara Regional Police Association exemplifies systemic transphobia and homophobia in policing, perpetuating a culture of distrust. This issue highlights accountability failures, emphasizing the need for broader community responsibility in ensuring respect and equality for marginalized groups.

STEADY, UNBROKEN: A River of Reconciliation

This piece reflects on the significance of National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, emphasizing the importance of listening to land, honoring Indigenous truths, and taking action towards reconciliation. The author highlights personal experiences along the Grand River, advocating for stewardship and shared responsibility.

Why the Debate Over Transgender Kids in Sports Misses the Point

This content critiques the persistent targeting of transgender individuals, especially trans women, by conservatives under false pretenses of fairness and biology. It highlights the contradictions in their arguments, emphasizing that their true motives revolve around exclusion and bigotry, ultimately questioning the kind of inclusive society we aspire to build.

- BEYOND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD: Black Community, Memory, and Freedom in St. Catharines

- On Not Disappearing

- I DIDN’T PLAN TO BECOME A TEACHER: The Students Who Made Me Stay

- JUSTICE ENDS WHERE POLICING BEGINS: The Shameful History of Policing The Gay and Trans Community in Canada

- RAISED BY PLACES UNSEEN: The Quiet Way Borneo Found Me